Every game travels a long path from its inventor to its players – by way of publishers and retailers. Complex discussions between the designer and editors yield a game that is as close as possible to the original idea, yet also as feasible as possible for mass production.

This development process covers every feature of a game – its content, the board graphics, the materials of the playing pieces, the box design, and much more. In some cases so much gets changed in the process that the end product bears hardly any resemblance to the prototype that the inventor originally showed the publisher.

The prototype serves to illustrate the game concept, and is also a field for experimentation. The board has to be properly conceived, the playing pieces have to have the right shapes and numbers, moves have to be checked over and over.

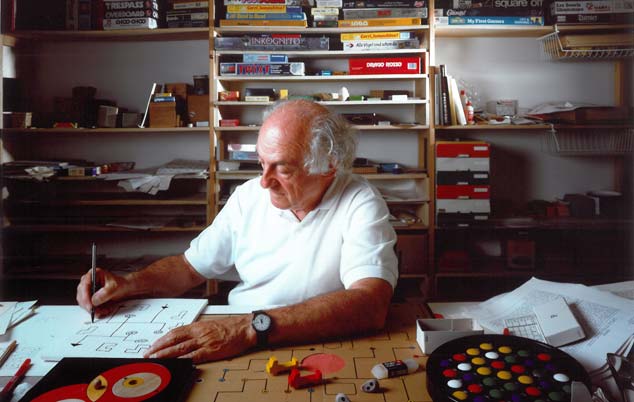

Alexander Randolph's estate included far more than 100 prototypes. Of course not every one of them made it to final publication. Most of his drafts are nevertheless complete games, with fully worked-out rules. Certain tricks of the trade and other features show up in multiple games; or there may be multiple drafts and prototypes for a single game, reflecting the various stages of the creative process.

Plainly unfinished prototypes and loose working materials, which make up a considerable portion of the legacy, clearly show that Randolph maintained his almost inexhaustible creativity till the end of this life.

You can see even from the prototypes how important careful aesthetic design was to him. While still in Japan, he worked with wood carvers to develop games like the multi-cornered Topolotoy puzzle. In Venice the hard-edged shapes became rounded, because of his collaboration with a wood lathe worker there. Thus his ideas came to be embodied in attractive playing pieces and high-quality wood boards. Angelo Dalla Venezia lent a unique look to Randolph's creations and legacy.

Randolph wasn't always happy with his games' final appearance. But he was well aware that if a game was too expensive or abstract, it couldn't sell at a profit. All the same, he insisted: "A game publisher who wants to be really successful for the long term has to look at his authors and their products the way a father looks at his children. It's not enough to give them enough pocket money – you also have to spend a little of your life's blood."

Randolph's ideas for games are minimalist. At first glance they usually look abstract, strategic, and not necessarily ready for the mass market. But his prototypes in particular radiate a certain elegance – often combined with a playful wink. His drawings and collections of ideas particularly show off his delight in simplicity and playfulness. He loved combining things, exploring new paths, designing labyrinths.

His most characteristic games are especially noteworthy for their tactical appeal. Fascinated by chess, and especially by the Japanese variant shogi, Randolph appreciated a strategic duel. His TwixT, especially famous among game aficionados, is a two-player contest based on the move that the knight makes in chess – an arrangement that had fascinated him since childhood.

One important part of Randolph's art was to take the principles of classic games and subtly manipulate them to form new games. The resulting games are based on clear basic ideas. Both boards and playing pieces are simple, moves have few variants, the rules are short and readily understandable. This simplicity is the great secret of his most profound games, like Ghosts!, Snail’s Pace Race, and Raj.

Randolph also adored poker and bluffing. Concealing one's identity, keeping an opponent off guard, misleading an enemy – a tactical game of cat and mouse brought onto a game board. It's an obvious theme in such games as Inkognito, Top Secret and Xe Queo!

But the most important feature of all for Randolph was the rules. Without them, there's no game. It was important to him to keep the rules as short, concise and simple as possible, even for his tactical games. There shouldn't be a long step between the rules and the fun of playing. All the same, a game needs rules if it's going to be fair. Except that unlike in life, we go along with the rules voluntarily and only temporarily: "I think we find the justice in games that we don't find in life."

Randolph also tried to make his games more accessible to families and occasional players by building on fairy tales, stories and genres. That was especially the case in the games he developed with collaborators, like Drachenfels (with Leo Colovini), The Forbidden City (with Johann Rüttinger) and Uagga Uagga! (with Hajo Bücken).

Randolph's biggest success, which won the Game of the Year Prize, was Enchanted Forest (Sagaland), which he developed jointly with Michel Matschoss at Sababurg Castle, under the original title Der König will nicht mehr ("The King Doesn't Want To Any More"). Enchanted Forest has sold millions of copies to date, in multiple languages.