The innovation of the Nuremberg Trials

The Major War Criminals Trial broke new legal ground in many respects. For the first time in history, states ruled by entirely different forms of government and constitutional systems joined forces to prosecute a defeated enemy in court. Instead of arbitrarily exacting revenge, the Allies sought to conduct a judicial proceeding in accordance with the rule of law. And for the first time in world history, individuals were personally held to account on the basis of international law.

The ramifications of Nuremberg

The Charter of the United Nations, which was adopted on June 26, 1945, attempted to secure world peace by establishing a system of international law. The Major War Criminals Trial and the London Charter of August 8, 1945, that provided the legal basis for this trial were fundamentally important to the development and enforcement of a system of international criminal law. Above all, the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg served as a model for today’s International Criminal Court in Den Haag.

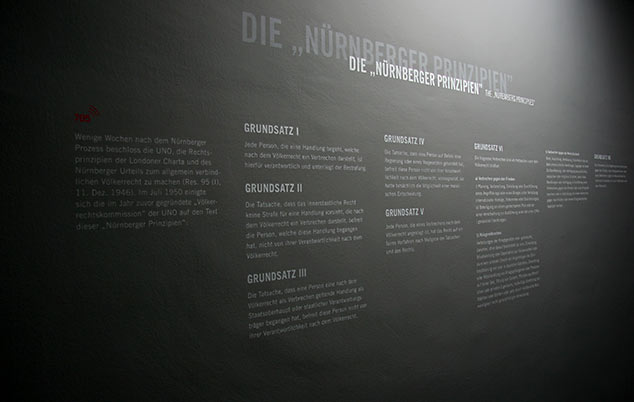

The Nuremberg Principles

In its first session of December 11, 1946, the General Assembly of the United Nations unanimously adopted a resolution affirming "the principles of international law acknowledged in the Charter of the Nuremberg Tribunal and in the judgment of this Tribunal." Four years later, the UN International Law Commission presented seven principles to be observed in drafting a Code of Crimes Against the Peace and Security of Mankind. This meant that the Nuremberg Principles no longer applied only to the crimes of the Nazi regime: they had assumed a universal validity.

1. Any person who commits an act which constitutes a crime under international law is responsible therefor and liable to punishment.

2. The fact that internal law does not impose a penalty for an act which constitutes a crime under international law does not relieve the person who committed the act from responsibility under international law.

3. The fact that a person who committed an act which constitutes a crime under international law acted as Head of State or responsible government official does not relieve him from responsibility under international law.

4. The fact that a person acted pursuant to order of his Government or of a superior does not relieve him from responsibility under international law, provided a moral choice was in fact possible to him.

5. Any person charged with a crime under international law has the right to a fair trial on the facts and law.

6. The crimes hereinafter set out are punishable as crimes under international law:

a. Crimes against the peace,

b. War crimes,

c. Crimes against humanity.

7. Complicity in the commission of a crime against peace, a war crime, or a crime against humanity as set forth in Principle VI is a crime under international law.